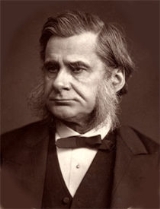

Thomas Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley was a British biologist. A prominent defender of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution, he was the grandfather of Julian, Aldous and Andrew Huxley. He was a critic of organised religion and devised the words "agnostic" and "agnosticism" to describe his own views.

Sourced

- I cannot but think that he who finds a certain proportion of pain and evil inseparably woven up in the life of the very worms, will bear his own share with more courage and submission; and will, at any rate, view with suspicion those weakly amiable theories of the Divine government, which would have us believe pain to be an oversight and a mistake, — to be corrected by and by. On the other hand, the predominance of happiness among living things — their lavish beauty — the secret and wonderful harmony which pervades them all, from the highest to the lowest, are equally striking refutations of that modern Manichean doctrine, which exhibits the world as a slave-mill, worked with many tears, for mere utilitarian ends.

There is yet another way in which natural history may, I am convinced, take a profound hold upon practical life, — and that is, by its influence over our finer feelings, as the greatest of all sources of that pleasure which is derivable from beauty.

- To a person uninstructed in natural history, his country or seaside stroll is a walk through a gallery filled with wonderful works of art, nine-tenths of which have their faces turned to the wall.

- "On the Educational Value of the Natural History Sciences" (1854)

- All truth, in the long run, is only common sense clarified.

- Extinguished theologians lie about the cradle of every science as the strangled snakes beside that of Hercules.

- A man has no reason to be ashamed of having an ape for his grandfather. If there was an ancestor whom I should feel shame in recalling it would rather be a man — a man of restless and versatile intellect — who not content with an equivocal success in his own sphere of activity, plunges into scientific questions with which he has no real acquaintance, only to obscure them with aimless rhetoric, and distract the attention of his hearers from the real point at issue by eloquent digressions and skilled appeals to religious prejudice.

- One account of his famous response to Samuel Wilberforce, who during a debate had sarcastically questioned: "whether he was descended from an ape on his grandmother's side or his grandfather's" (30 June 1860), as quoted in Life and Letters of Thomas Henry Huxley F.R.S (1900) edited by Leonard Huxley. There were no precise transcripts of this exchange made at the time, but only various accounts which were made afterwards, in the journals and memoirs of others. Other accounts assert that after Wilberforce's query he declared to Sir Benjamin Brodie "The Lord hath delivered him into my hands" rose from his seat, gave a thorough defense of Darwin's theories, and at the end concluded: "I would rather be the offspring of two apes than be a man and afraid to face the truth."

- If the question is put to me would I rather have a miserable ape for a grandfather or a man highly endowed by nature and possessed of great means of influence and yet who employs these faculties and that influence for the mere purpose of introducing ridicule into a grave scientific discussion, I unhesitatingly affirm my preference for the ape.

- Response, as quoted in Harvest of a Quiet Eye (1977) by Alan L. Mackay.

- The Bishop rose, and in a light scoffing tone, florid and he assured us there was nothing in the idea of evolution; rock-pigeons were what rock-pigeons had always been. Then, turning to his antagonist with a smiling insolence, he begged to know, was it through his grandfather or his grandmother that he claimed his descent from a monkey? On this Mr Huxley slowly and deliberately arose. A slight tall figure stern and pale, very quiet and very grave, he stood before us, and spoke those tremendous words — words which no one seems sure of now, nor I think, could remember just after they were spoken, for their meaning took away our breath, though it left us in no doubt as to what it was. He was not ashamed to have a monkey for his ancestor; but he would be ashamed to be connected with a man who used great gifts to obscure the truth. No one doubted his meaning and the effect was tremendous. One lady fainted and had to carried out: I, for one, jumped out of my seat; and when in the evening we met at Dr Daubeney's, every one was eager to congratulate the hero of the day.

- Another account, by Mrs. Isabella Sidgwick in "A Grandmother's Tales"; Macmillan's Magazine LXXVIII, No. 468 (October 1898)

- Life is too short to occupy oneself with the slaying of the slain more than once.

- One of a series of exchanges when Richard Owen repeated generally repudiated claims about the Gorilla brain in a Royal Institution lecture. Athenaeum (13 April 1861) p.498; Browne Vol 2, p.159

- The fact is he made a prodigious blunder in commencing the attack, and now his only chance is to be silent and let people forget the exposure. I do not believe that in the whole history of science there is a case of any man of reputation getting himself into such a contemptible position.

- About Richard Owen's view on human and ape brains, in a letter to J.D. Hooker (27 April 1861)

- I have never had the least sympathy with the a priori reasons against orthodoxy, and I have by nature and disposition the greatest possible antipathy to all the atheistic and infidel school. Nevertheless I know that I am, in spite of myself, exactly what the Christian would call, and, so far as I can see, is justified in calling, atheist and infidel.

- Letter to Charles Kingsley (6 May 1863)

- I do not mean to suggest that scientific differences should be settled by universal suffrage, but I do conceive that solid proofs must be met by something more than empty and unsupported assertions. Yet during the two years through which this preposterous controversy has dragged its weary length, Professor Owen has not ventured to bring forward a single preparation in support of his often-repeated assertions.

The case stands thus, therefore: Not only are the statements made by me in consonance with the doctrines of the best older authorities, and with those of all recent investigators, but I am quite ready to demonstrate them on the first monkey that comes to hand; while Professor Owen's assertions are not only in diametrical opposition to both old and new authorities, but he has not produced, and, I will add, cannot produce, a single preparation which justifies them.- A Succinct History of the Controversy respecting the Cerebral Structure of Man and the Apes, in Evidence as to Man's place in Nature (1863)

- The method of scientific investigation is nothing but the expression of the necessary mode of working of the human mind.

- It may be quite true that some negroes are better than some white men; but no rational man, cognisant of the facts, believes that the average negro is the equal, still less the superior, of the average white man. And, if this be true, it is simply incredible that, when all his disabilities are removed, and our prognathous relative has a fair field and no favour, as well as no oppressor, he will be able to compete successfully with his bigger-brained and smaller-jawed rival, in a contest which is to be carried on by thoughts and not by bites. The highest places in the hierarchy of civilisation will assuredly not be within the reach of our dusky cousins, though it is by no means necessary that they should be restricted to the lowest.

But whatever the position of stable equilibrium into which the laws of social gravitation may bring the negro, all responsibility for the result will henceforward lie between nature and him. The white man may wash his hands of it, and the Caucasian conscience be void of reproach for evermore. And this, if we look to the bottom of the matter, is the real justification for the abolition policy.

The doctrine of equal natural rights may be an illogical delusion; emancipation may convert the slave from a well-fed animal into a pauperised man; mankind may even have to do without cotton-shirts; but all these evils must be faced if the moral law, that no human being can arbitrarily dominate over another without grievous damage to his own nature, be, as many think, as readily demonstrable by experiment as any physical truth. If this be true, no slavery can be abolished without a double emancipation, and the master will benefit by freedom more than the freed-man.- "Emancipation — Black and White" (1865), later published in Lay Sermons, Addresses, and Reviews (1871) Comments accepting many racist and sexist assumptions made in the context of rejecting oppressions based on racist and sexist arguments. More information is available at the Talk Origins Archive

- Let us have "sweet girl graduates" by all means. They will be none the less sweet for a little wisdom; and the "golden hair" will not curl less gracefully outside the head by reason of there being brains within.

- "Emancipation — Black and White" (1865)

- The improver of natural knowledge absolutely refuses to acknowledge authority, as such. For him, scepticism is the highest of duties; blind faith the one unpardonable sin. And it cannot be otherwise, for every great advance in natural knowledge has involved the absolute rejection of authority, the cherishing of the keenest scepticism, the annihilation of the spirit of blind faith; and the most ardent votary of science holds his firmest convictions, not because the men he most venerates hold them; not because their verity is testified by portents and wonders; but because his experience teaches him that whenever he chooses to bring these convictions into contact with their primary source, Nature — whenever he thinks fit to test them by appealing to experiment and to observation — Nature will confirm them. The man of science has learned to believe in justification, not by faith, but by verification.

- M. Comte's philosophy, in practice, might be compendiously described as Catholicism minus Christianity.

- The great tragedy of Science — the slaying of a beautiful hypothesis by an ugly fact.

- Presidential Address at the British Association, "Biogenesis and abiogenesis" (1870); later published in Collected Essays, Vol. 8, p. 229

- If some great Power would agree to make me always think what is true and do what is right, on condition of being turned into a sort of clock and wound up every morning before I got out of bed, I should instantly close with the offer. The only freedom I care about is the freedom to do right; the freedom to do wrong I am ready to part with on the cheapest terms to any one who will take it of me.

- I can assure you that there is the greatest practical benefit in making a few failures early in life. You learn that which is of inestimable importance — that there are a great many people in the world who are just as clever as you are. You learn to put your trust, by and by, in an economy and frugality of the exercise of your powers, both moral and intellectual; and you very soon find out, if you have not found it out before, that patience and tenacity of purpose are worth more than twice their weight of cleverness.

- The only good that I can see in the demonstration of the truth of "Spiritualism" is to furnish an additional argument against suicide. Better live a crossing-sweeper than die and be made to talk twaddle by a "medium" hired at a guinea a séance.

- Review in the Daily News (17 October 1871), quoted in Life and Letters of Thomas Henry Huxley F.R.S (1900) edited by Leonard Huxley, Vol. 1, p. 452

- I do not advocate burning your ship to get rid of the cockroaches.

- Said in reference to those who wished to abolish all religious teaching, rather than freeing state education from Church controls, in Critiques and Addresses (1873) p. 90.

- That mysterious independent variable of political calculation, Public Opinion.

- In an ideal University, as I conceive it, a man should be able to obtain instruction in all forms of knowledge, and discipline in the use of all the methods by which knowledge is obtained. In such a University, the force of living example should fire the student with a noble ambition to emulate the learning of learned men, and to follow in the footsteps of the explorers of new fields of knowledge. And the very air he breathes should be charged with that enthusiasm for truth, that fanaticism of veracity, which is a greater possession than much learning; a nobler gift than the power of increasing knowledge; by so much greater and nobler than these, as the moral nature of man is greater than the intellectual; for veracity is the heart of morality.

- Universities, Actual and Ideal (1874)

- The man who is all morality and intellect, although he may be good and even great, is, after all, only half a man.

- Universities, Actual and Ideal (1874)

- Becky Sharp's acute remark that it is not difficult to be virtuous on ten thousand a year, has its application to nations; and it is futile to expect a hungry and squalid population to be anything but violent and gross.

- Logical consequences are the scarecrows of fools and the beacons of wise men.

- Size is not grandeur, and territory does not make a nation.

- Perhaps the most valuable result of all education is the ability to make yourself do the thing you have to do, when it ought to be done, whether you like it or not; it is the first lesson that ought to be learned; and, however early a man's training begins, it is probably the last lesson that he learns thoroughly.

- The great end of life is not knowledge but action.

- "Technical Education" (1877)

- The saying that a little knowledge is a dangerous thing is, to my mind, a very dangerous adage. If knowledge is real and genuine, I do not believe that it is other than a very valuable possession, however infinitesimal its quantity may be. Indeed, if a little knowledge is dangerous, where is the man who has so much as to be out of danger?

- History warns us, however, that it is the customary fate of new truths to begin as heresies and to end as superstitions; and, as matters now stand, it is hardly rash to anticipate that, in another twenty years, the new generation, educated under the influences of the present day, will be in danger of accepting the main doctrines of the 'Origin of Species' with as little reflection, and it may be with as little justification, as so many of our contemporaries, twenty years ago, rejected them. Against any such a consummation let us all devoutly pray; for the scientific spirit is of more value than its products, and irrationally held truths may be more harmful than reasoned errors.

- "The Coming of Age of The Origin of Species" (1880); Collected Essays, vol. 2

- The antagonism between science and religion, about which we hear so much, appears to me to be purely factitious — fabricated, on the one hand, by short-sighted religious people who confound a certain branch of science, theology, with religion; and, on the other, by equally short-sighted scientific people who forget that science takes for its province only that which is susceptible of clear intellectual comprehension; and that, outside the boundaries of that province, they must be content with imagination, with hope, and with ignorance.

- Science ... commits suicide when it adopts a creed.

- I am too much of a sceptic to deny the possibility of anything — especially as I am now so much occupied with theology — but I don't see my way to your conclusion.

- Letter to Herbert Spencer (22 March 1886) This is often quoted with a variant spelling as: I am too much of a skeptic to deny the possibility of anything.

- The foundation of morality is to have done, once and for all, with lying; to give up pretending to believe that for which there is no evidence, and repeating unintelligible propositions about things beyond the possibilities of knowledge.

- Missionaries, whether of philosophy or of religion, rarely make rapid way, unless their preachings fall in with the prepossessions of the multitude of shallow thinkers, or can be made to serve as a stalking-horse for the promotion of the practical aims of the still larger multitude, who do not profess to think much, but are quite certain they want a great deal. Rousseau's writings are so admirably adapted to touch both these classes that the effect they produced, especially in France, is easily intelligible.

- The doctrine that all men are, in any sense, or have been, at any time, free and equal, is an utterly baseless fiction.

- "On The Natural Inequality of Men" (January 1890)

- The mediaeval university looked backwards: it professed to be a storehouse of old knowledge... The modern university looks forward: it is a factory of new knowledge.

- Letter to E. Ray Lankester (11 April 1892) Huxley Papers, Imperial College: 30.448

- Social progress means a checking of the cosmic process at every step and the substitution for it of another, which may be called the ethical process; the end of which is not the survival of those who may happen to be the fittest, in respect of the whole of the conditions which obtain, but of those who are ethically the best.

- Abram, Abraham became

By will divine

Let pickled Brian's name

Be changed to Brine!- Poem in letter Joseph Dalton Hooker (4 December 1894) in response to hearing that Hooker's son had fallen into a salt vat. Huxley papers at Imperial College London HP 2.454.

- I trust that I have now made amends for any ambiguity, or want of fulness, in my previous exposition of that which I hold to be the essence of the Agnostic doctrine. Henceforward, I might hope to hear no more of the assertion that we are necessarily Materialists, Idealists, Atheists, Theists, or any other ists, if experience had led me to think that the proved falsity of a statement was any guarantee against its repetition. And those who appreciate the nature of our position will see, at once, that when Ecclesiasticism declares that we ought to believe this, that, and the other, and are very wicked if we don't, it is impossible for us to give any answer but this: We have not the slightest objection to believe anything you like, if you will give us good grounds for belief; but, if you cannot, we must respectfully refuse, even if that refusal should wreck morality and insure our own damnation several times over. We are quite content to leave that to the decision of the future. The course of the past has impressed us with the firm conviction that no good ever comes of falsehood, and we feel warranted in refusing even to experiment in that direction.

- Try to learn something about everything and everything about something.

- A favorite comment, inscribed on his memorial at Ealing, quoted in Nature Vol. XLVI (30 October 1902), p. 658

- For myself I say deliberately, it is better to have a millstone tied round the neck and be thrown into the sea than to share the enterprises of those to whom the world has turned, and will turn, because they minister to its weaknesses and cover up the awful realities which it shudders to look at.

- Aphorism #367, in Aphorisms and Reflections (1907) edited by Henrietta A. Huxley, his widow.

- God give me strength to face a fact though it slay me.

- As quoted in Nature Vol. 149 (Jan-Jun) 1942 p. 291, and A Philosophy for Our Time (1954) by Bernard Mannes Baruch, p. 13

- Not far from the invention of fire... we must rank the invention of doubt.

- Collected Essays vol 6, viii; quoted in T. H. Huxley: Scientist, Humanist, and Educator (1950) by Cyril Bibby, p. 257

Reply to Charles Kingsley (1860)

- Letter of reply to Charles Kingsley (23 September 1860), who had offered him consolation after Huxley's young son had died some days earlier

- My convictions, positive and negative, on all the matters of which you speak, are of long and slow growth and are firmly rooted. But the great blow which fell on me seemed to stir them to their foundation, and had I lived a couple of centuries earlier I could have fancied a devil scoffing at me and them — and asking me what profit it was to have stripped myself of the hopes and consolations of the mass of mankind? To which my only reply was and is — Oh devil! Truth is better than much profit. I have searched over the grounds of my belief, and if wife and child and name and fame were all to be lost to me one after the other as the penalty, still I will not lie.

- I neither deny nor affirm the immortality of man. I see no reason for believing in it, but, on the other hand, I have no means of disproving it.

- Give me such evidence as would justify me in believing in anything else and I will believe that. Why should I not? It is not half so wonderful as the conservation of force, or the indestructibility of matter. Whoso clearly appreciates all that is implied in the falling of a stone can have no difficulty about any doctrine simply on account of its marvelousness But the longer I live, the more obvious it is to me that the most sacred act of a man's life is to say and to feel, 'I believe such and such to be true.' All the greatest rewards and all the heaviest penalties of existence cling about that act. The universe is one and the same throughout; and if the condition of my success in unraveling some little difficulty of anatomy or physiology is that I shall rigorously refuse to put faith in that which does not rest on sufficient evidence, I cannot believe that the great mysteries of existence will be laid open to me on other terms.... I know what I mean when I say I believe in the law of the inverse squares, and I will not rest my life and hopes upon weaker convictions. I dare not if I would.

- Science has taught... me to be careful how I adopt a view which jumps with my preconceptions, and to require stronger evidence for such belief than for one to which I was previously hostile.

My business is to teach my aspirations to conform themselves to fact, not to try and make facts harmonise with my aspirations.

- Science seems to me to teach in the highest and strongest manner the great truth which is embodied in the Christian conception of entire surrender to the will of God. Sit down before fact as a little child, be prepared to give up every preconceived notion, follow humbly wherever and to whatever abysses nature leads, or you shall learn nothing. I have only begun to learn content and peace of mind since I have resolved at all risks to do this.

- Life cannot exist without a certain conformity to the surrounding universe — that conformity involves a certain amount of happiness in excess of pain. In short, as we live we are paid for living.

- The absolute justice of the system of things is as clear to me as any scientific fact. The gravitation of sin to sorrow is as certain as that of the earth to the sun, and more so–for experimental proof of the fact is within reach of us all–nay, is before us all in our own lives, if we had but the eyes to see it.

A Liberal Education and Where to Find It (1868)

- For every man the world is as fresh as it was at the first day, and as full of untold novelties for him who has the eyes to see them.

- The life, the fortune, and the happiness of every one of us, and, more or less, of those who are connected with us, do depend upon our knowing something of the rules of a game infinitely more difficult and complicated than chess. It is a game which has been played for untold ages, every man and woman of us being one of the two players in a game of his or her own. The chessboard is the world, the pieces are the phenomena of the universe, the rules of the game are what we call the laws of Nature. The player on the other side is hidden from us. We know that his play is always fair, just, and patient. But also we know, to our cost, that he never overlooks a mistake, or makes the smallest allowance for ignorance. To the man who plays well, the highest stakes are paid, with that sort of overflowing generosity with which the strong shows delight in strength. And one who plays ill is checkmated — without haste, but without remorse.

- Education is the instruction of the intellect in the laws of Nature, under which name I include not merely things and their forces, but men and their ways; and the fashioning of the affections and of the will into an earnest and loving desire to move in harmony with those laws. For me, education means neither more nor less than this. Anything which professes to call itself education must be tried by this standard, and if it fails to stand the test, I will not call it education, whatever may be the force of authority, or of numbers, upon the other side.

- The only medicine for suffering, crime, and all the other woes of mankind, is wisdom.

On a Piece of Chalk (1868)

- If a well were sunk at our feet in the midst of the city of Norwich, the diggers would very soon find themselves at work in that white substance almost too soft to be called rock, with which we are all familiar as "chalk."

- The chalk is no unimportant element in the masonry of the earth’s crust, and it impresses a peculiar stamp, varying with the conditions to which it is exposed, on the scenery of the districts in which it occurs.

- What is this wide-spread component of the surface of the earth? and whence did it come?

You may think this no very hopeful inquiry. You may not unnaturally suppose that the attempt to solve such problems as these can lead to no result, save that of entangling the inquirer in vague speculations, incapable of refutation and of verification.

If such were really the case, I should have selected some other subject than a "piece of chalk" for my discourse. But, in truth, after much deliberation, I have been unable to think of any topic which would so well enable me to lead you to see how solid is the foundation upon which some of the most startling conclusions of physical science rest.

- A great chapter of the history of the world is written in the chalk. Few passages in the history of man can be supported by such an overwhelming mass of direct and indirect evidence as that which testifies to the truth of the fragment of the history of the globe, which I hope to enable you to read, with your own eyes, tonight.

Let me add, that few chapters of human history have a more profound significance for ourselves. I weigh my words well when I assert, that the man who should know the true history of the bit of chalk which every carpenter carries about in his breeches-pocket, though ignorant of all other history, is likely, if he will think his knowledge out to its ultimate results, to have a truer, and therefore a better, conception of this wonderful universe, and of man’s relation to it, than the most learned student who is deep-read in the records of humanity and ignorant of those of Nature.

- The language of the chalk is not hard to learn, not nearly so hard as Latin, if you only want to get at the broad features of the story it has to tell; and I propose that we now set to work to spell that story out together.

- Only two suppositions seem to be open to us — Either each species of crocodile has been specially created, or it has arisen out of some pre-existing form by the operation of natural causes.

Choose your hypothesis; I have chosen mine. I can find no warranty for believing in the distinct creation of a score of successive species of crocodiles in the course of countless ages of time.

- A small beginning has led us to a great ending. If I were to put the bit of chalk with which we started into the hot but obscure flame of burning hydrogen, it would presently shine like the sun. It seems to me that this physical metamorphosis is no false image of what has been the result of our subjecting it to a jet of fervent, though nowise brilliant, thought to-night. It has become luminous, and its clear rays, penetrating the abyss of the remote past, have brought within our ken some stages of the evolution of the earth. And in the shifting "without haste, but without rest" of the land and sea, as in the endless variation of the forms assumed by living beings, we have observed nothing but the natural product of the forces originally possessed by the substance of the universe.

On the Reception of the Origin of Species (1887)

- Since Lord Brougham assailed Dr Young, the world has seen no such specimen of the insolence of a shallow pretender to a Master in Science as this remarkable production, in which one of the most exact of observers, most cautious of reasoners, and most candid of expositors, of this or any other age, is held up to scorn as a "flighty" person, who endeavours "to prop up his utterly rotten fabric of guess and speculation," and whose "mode of dealing with nature" is reprobated as "utterly dishonourable to Natural Science."

And all this high and mighty talk, which would have been indecent in one of Mr. Darwin's equals, proceeds from a writer whose want of intelligence, or of conscience, or of both, is so great, that, by way of an objection to Mr. Darwin's views, he can ask, "Is it credible that all favourable varieties of turnips are tending to become men?"; who is so ignorant of paleontology, that he can talk of the "flowers and fruits" of the plants of the Carboniferous epoch; of comparative anatomy, that he can gravely affirm the poison apparatus of the venomous snakes to be "entirely separate from the ordinary laws of animal life, and peculiar to themselves"...

Nor does the reviewer fail to flavour this outpouring of preposterous incapacity with a little stimulation of the odium theologicum. Some inkling of the history of the conflicts between Astronomy, Geology, and Theology, leads him to keep a retreat open by the proviso that he cannot "consent to test the truth of Natural Science by the word of Revelation;" but, for all that, he devotes pages to the exposition of his conviction that Mr. Darwin's theory "contradicts the revealed relation of the creation to its Creator," and is "inconsistent with the fulness of his glory."

If I confine my retrospect of the reception of the 'Origin of Species' to a twelvemonth, or thereabouts, from the time of its publication, I do not recollect anything quite so foolish and unmannerly as the Quarterly Review article...- Huxley's commentary on the Samuel Wilberforce review of the Origin of Species in the Quarterly Review

- My reflection when I first made myself master of the central idea of the Origin was, "How extremely stupid not to have thought of that."

- The known is finite, the unknown infinite; intellectually we stand on an islet in the midst of an illimitable ocean of inexplicability. Our business in every generation is to reclaim a little more land, to add something to the extent and the solidity of our possessions.

Agnosticsim (1889)

- "Agnosticsim" published in The Nineteenth Century (February 1889) ; also in Christianity and Agnosticism (1889)

- Agnosticism is not properly described as a "negative" creed, nor indeed as a creed of any kind, except in so far as it expresses absolute faith in the validity of a principle which is as much ethical as intellectual. This principle may be stated in various ways, but they all amount to this: that it is wrong for a man to say that he is certain of the objective truth of any proposition unless he can produce evidence which logically justifies that certainty. This is what agnosticism asserts; and, in my opinion, it is all that is essential to agnosticism. That which agnostics deny and repudiate as immoral is the contrary doctrine, that there are propositions which men ought to believe, without logically satisfactory evidence; and that reprobation ought to attach to the profession of disbelief in such inadequately supported propositions. The justification of the agnostic principle lies in the success which follows upon its application, whether in the field of natural or in that of civil history; and in the fact that, so far as these topics are concerned, no sane man thinks of denying its validity.

- The extent of the region of the uncertain, the number of the problems the investigation of which ends in a verdict of not proven, will vary according to the knowledge and the intellectual habits of the individual agnostic. I do not very much care to speak of anything as unknowable. What I am sure about is that there are many topics about which I know nothing, and which, so far as I can see, are out of reach of my faculties. But whether these things are knowable by any one else is exactly one of those matters which is beyond my knowledge, though I may have a tolerably strong opinion as to the probabilities of the case.

- When I reached intellectual maturity and began to ask myself whether I was an atheist, a theist, or a pantheist; a materialist or an idealist; Christian or a freethinker; I found that the more I learned and reflected, the less ready was the answer; until, at last, I came to the conclusion that I had neither art nor part with any of these denominations, except the last. The one thing in which most of these good people were agreed was the one thing in which I differed from them. They were quite sure they had attained a certain "gnosis," — had, more or less successfully, solved the problem of existence; while I was quite sure I had not, and had a pretty strong conviction that the problem was insoluble.

So I took thought, and invented what I conceived to be the appropriate title of "agnostic." It came into my head as suggestively antithetic to the "gnostic" of Church history, who professed to know so much about the very things of which I was ignorant. To my great satisfaction the term took.

Misattributed

- The primary purpose of a liberal education is to make one's mind a pleasant place in which to spend one's time.

- Sydney J. Harris, as quoted in The Routledge Dictionary of Quotations (1989) by Robert Andrews; also quoted as: "...a pleasant place in which to spend one's leisure."

Quotations about Huxley

- Huxleyism: the theory of the anthropoid descent of man and its inevitable consequences.

- Clarence Edwin Ayres, in Huxley (1929) p. 242

- Darwin's bulldog was patently a man of almost puritanical uprightness.

- Cyril Bibby in 'T.H. Huxley: Scientist, Humanist and Educator (1959) p. 56

- It was worth being born to have known Huxley.

- Edward Clodd, biologist and biographer in Memories (1916), p. 40

- I think his tone is much too vehement.

- Charles Darwin in letter to Joseph Dalton Hooker about Huxley's Royal Institution lecture in 1854

- My good and kind agent for the propagation of the Gospel; i.e. the Devil's gospel.

- This humorous remark closes a letter by Charles Darwin, to Huxley (8 August 1860), but it can also be interpreted as referring to Louis Agassiz, rather than Huxley himself.

- "Pope Huxley"

- Richard Holt Hutton in the title of an article in which he accuses Huxley of too great a degree of certitude in some of his arguments. The Spectator (29 January 1870)

- Huxley, I believe, was the greatest Englishman of the Nineteenth Century — perhaps the greatest Englishman of all time.

- H. L. Mencken in "Thomas Henry Huxley" in the Baltimore Evening Sun (4 May 1925)

- All of us owe a vast debt to Huxley, especially all of us of English speech, for it was he, more than any other man, who worked that great change in human thought which marked the Nineteenth Century.

- H. L. Mencken in "Thomas Henry Huxley" in the Baltimore Evening Sun (4 May 1925)

- The row was over Darwinism, but before it ended Darwinism was almost forgotten. What Huxley fought for was something far greater: the right of civilized men to think freely and speak freely, without asking leave of authority, clerical or lay. How new that right is! And yet how firmly held! Today it would be hard to imagine living without it. No man of self-respect, when he has a thought to utter, pauses to wonder what the bishops will have to say about it. The views of bishops are simply ignored. Yet only sixty years ago they were still so powerful that they gave Huxley the battle of his life.

- H. L. Mencken in "Thomas Henry Huxley" in the Baltimore Evening Sun (4 May 1925)

- From [1854] until 1885 Huxley's labours extended over the widest field of biology and philosophy ever covered by any naturalist with the single exception of Aristotle.

- Henry Fairfield Osborn in Impressions of Great Naturalists (1924) p. 107-8

- Huxley gave the death-blow not only to Owen's theory of the skull but also to Owen's hitherto unchallenged prestige.

- Henry Fairfield Osborn in Impressions of Great Naturalists. (1924) p. 113

- The illustrious comparative anatomist, Huxley, Darwin's great general in the battles that had to be fought, but not a naturalist, far less a student of living nature.

- Edward Bagnall Poulton in Charles Darwin and the Origin of Species (1909) p. 58

- A man who was always taking two irons out of the fire and putting three in.

- Herbert Spencer

- The papers are printed and circulated among the members, and begin to form a little volume. Among the contributors have been Archbishop Huxley and Professor Manning.

- Bishop Connop Thirlwall Letters to a Friend (1881) p. 317

- I believed that he was the greatest man I was ever likely to meet, and I believe that all the more firmly today.

- H. G. Wells in The Royal College of Science Magazine (1901)

- If he has a fault it is... that like Caesar, he is ambitious... cutting up apes is his forté, cutting up men is his foible.

- "A Devonshire Man" in the Pall Mall Gazette (18 January 1870)

- I'm a good Christian woman — I'm not an infidel like you!

- Huxley's cook Bridget, after being scolded for drunkenness, as quoted in Huxley : From Devil's Disciple to Evolution's High Priest (1997) by Adrian Desmond

- Oh, there goes Professor Huxley; faded but still fascinating.

- Woman overheard at Dublin meeting of the British Association of 1878, quoted in The Life and Letters of Thomas Henry Huxley (1900) by Leonard Huxley, p. 80

- His voice was low, clear and distinct... Professor Huxley's method is slow, precise, and clear, and he guards the positions that he takes with astuteness and ability. He does not utter anything in reckless fashion which conviction sometimes countenances and excuses, but rather with the deliberation that research and close inquiry foster.

- Newspaper account of speech at opening of Johns Hopkins University (13 September 1876), quoted in The Great Influenza : The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History (2005) by John M. Barry, p. 13

- The doctrine that all men are, in any sense, or have been, at any time, free and equal, is an utterly baseless fiction.