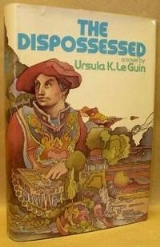

The Dispossessed

The Dispossessed is a 1974 utopian science fiction novel by Ursula K. Le Guin, set in the same fictional universe as The Left Hand of Darkness (the Hainish Cycle). The book won both Hugo and Nebula awards in 1975, and achieved a degree of literary recognition unusual for science fiction works.

Sourced

(Page numbers in parentheses refer to the HarperCollins/Eos 2001 paperback edition, ISBN 0061054887.)- Like all walls it was ambiguous, two-faced. What was inside it and what was outside it depended upon which side of it you were on. Looked at from one side, the wall enclosed a barren sixty-acre field called the Port of Anarres. [...] It was in fact a quarantine. The wall shut in not only the landing field but also the ships that came down out of space, and the men that came on the ships, and the worlds they came from, and the rest of the universe. It enclosed the universe, leaving Anarres outside, free. Looked at from the other side, the wall enclosed Anarres: the whole planet was inside it, a great prison camp , cut off from other worlds and other men, in quarantine.

- Ch. 1 (pp. 1–2)

- It is of the nature of idea to be communicated: written, spoken, done. The idea is like grass. It craves light, likes crowds, thrives on crossbreeding, grows better for being stepped on.

- Ch. 3 (p. 72)

- He had assumed that if you removed a human being's natural incentive to work—his initiative, his spontaneous creative energy—and replaced it with external motivation and coercion, he would become a lazy and careless worker. [...] The lure and compulsion of profit was evidently a much more effective replacement of the natural initiative than he had been led to believe.

- Ch. 3 (p.82)

- No doors were locked, few shut. There were no disguises and no advertisements. It was all there, all the work, all the life of the city, open to the eye and to the hand.

- Ch. 4 (p. 99)

- A child free from the guilt of ownership and the burden of economic competition will grow up with the will to do what needs doing and the capacity for joy in doing it. It is useless work that darkens the heart. The delight of the nursing mother, of the scholar, of the successful hunter, of the good cook, of the skilful maker, of anyone doing needed work and doing it well—this durable joy is perhaps the deepest source of human affection, and of sociality as a whole.

- Ch. 8 (p. 247)

- There's a point, around age twenty, [...] when you have to choose whether to be like everybody else the rest of your life, or to make a virtue of your peculiarities.

- Ch. 8 (p. 250)

- The individual cannot bargain with the State. The State recognizes no coinage but power: and it issues the coins itself.

- Ch. 9 (p. 272)

- It is our suffering that brings us together. It is not love. Love does not obey the mind, it turns to hate when forced. The bond that binds us is beyond choice. We are brothers. We are brothers in what we share. In pain, which each of us must suffer alone, in hunger, in poverty, in hope, we know our brotherhood. We know it, because we have been forced to learn it. We know that there is no help for us but from one another, that no hand will save us if we do not reach out our hand. And the hand that you reach out is empty, as mine is. You have nothing. You possess nothing. You own nothing. You are free. All you have is what you are, and what you give.

- Ch. 9 (p. 300) — from the protagonist's major speech.

- You cannot buy the Revolution. You cannot make the Revolution. You can only be the Revolution. It is in your spirit or, it is nowhere.

- Ch. 9 (p. 301)

- With the myth of the State out of the way, the real mutuality and reciprocity of society and individual became clear. Sacrifice might be demanded of the individual, but never compromise: for though only the society could give security and stability, only the individual, the person, had the power of moral choice—the power of change, the essential function of life. The Odonian society was conceived as a permanent revolution, and revolution begins in the thinking mind.

- Ch. 10 (p. 333)

- Urras is a box, a package, with all the beautiful wrapping of blue sky and meadows and forests and great cities. And you open the box, and what is inside it? A black cellar full of dust, and a dead man. A man whose hand was shot off because he held it out to others.

- Ch. 11 (p. 347)

- What we're after is to remind ourselves that we didn't come to Anarres for safety, but for freedom. If we must all agree, all work together, we're no better than a machine. If an individual can't work in solidarity with his fellows, it's his duty to work alone. His duty and his right. We have been denying people that right. We've been saying, more and more often, you must work with the others, you must accept the rule of the majority. But any rule is tyranny. The duty of the individual is to accept no rule, to be the initiator of his own acts, to be responsible. Only if he does so will the society live, and change, and adapt, and survive. We are not subjects of a State founded upon law, but members of a society founded upon revolution. Revolution is our obligation: our hope of evolution.

- Ch. 12 (p. 359)

- The Revolution is in the individual spirit, or it is nowhere. It is for all, or it is nothing. If it is seen as having any end, it will never truly begin. We can't stop here. We must go on. We must take the risks.

- Ch. 12 (p. 359)